I’ve put this off for a while now. It’s as if putting it into words means that it’s all real. Which I guess it is. On April 12 – Easter Sunday – my father died. Even now, a month on, that sentence makes little sense to me.

Trying to write a remembrance for your father’s life is like cupping your hands and trying to seize an entire great lake. You want to net the entirety of his existence but the vast majority slips through your fingers, leaving you feeling bereft and lost.

As I felt the night he died.

Parents aren’t supposed to die. Oh, we objectively know that they will. But the rational consciousness cannot make peace with the emotional knowledge that is a parent in a child’s mind. And so, it rebels. Recoils from the fact that death, as my eight year-old nephew pointed out, is inevitable.

As an aside, we might want to keep an eye on that one.

My father was a paradox. There is no better or worse way to describe him. He was born in 1937, at the University of Michigan. This was a fact that both of us did our best to banish from the scarlet and gray hue of our The Ohio State University-addled minds. He was born on Hitler’s birthday – at a time when Hitler was still alive to celebrate it. Dad would often joke that he was born to redeem the day. Six days after dad was born, the Nazi Condor Legion bombed Geurnica in Spain, killing hundreds of innocent civilians and presaging the terrible bombing raids over cities in World War II. Dad was born into a world on the brink of madness. And I think he felt it.

I only knew my father as a man in his fifties and older. While I recognize the rail-straight young-looking man in the photos, he’s not the dad that I recognize. By the time I could gather memories, dad had already lost most of his thin blonde hair turned gray, which he forever parted over the top of his head to hide the bald spot. If all is vanity, it was one of the few he allowed himself.

Growing up, people would ask, “Oh, what does your father do?” And I would smile and pause, trying to find some easy way to say “my dad last held a conventional job sometime in the ‘sixties before he sold his bar in Chapel Hill and he and my mom decided to live simply, on the land, searching for Catholic community, which led them, with my sisters, from North Carolina to Virginia to Ohio – where they had me – and then to a handful of lesser cults and one pretty crazy one, while continuing to live in voluntary poverty as dad gardened and my Columbia-educated mother homeschooled all three of us until we finally settled down in rural Ohio and she went back to work, and this is totally normal, right?”

I usually just said that he gardened. Which was true.

I’m not sure exactly when dad’s tough hands first went into the soil. But it was a life-changing moment. Soil was around us at all times, growing up. Dad would start his seedlings even as the snow fell, under bright grow-lights in the basement or in the oven, because heat and light. I don’t think it ever registered to me that most people didn’t have plants in the oven as kids. His gardens were one of his great passions. As a boy, I would walk the brown beaten path out from the old tumble-down house we lived in at the time, out to the long and verdant swathes of dad’s gardens. Acres of them.

He’d be out there, arms lean and brown from the sun, hoe turning over fresh earth, or he’d be carrying the buckets of water up from the spring to irrigate his rows. We had no running water, so he would make this shoulder-straining trip time after time, or find a way to engineer an old diesel-powered engine to pump water up to the gardens. I would stump along behind him, all four years of my existence very seriously concentrating on my tiny yellow watering can. He could hear me behind him, muttering to myself, “Help daddy, help daddy.”

The winters were cold. We heated with a cast-iron wood stove that would keep the main family room delightfully warm while the rest of the house was so cold that I still remember the nighttime cold-footed scamper to my room, plunging into deep covers to await the coming of a parent bearing stories and prayers. Dad would cut dead trees in the woods, carrying long trunks on his shoulder, whistling something, probably “On the Steppes of Central Asia.” I’d follow behind, and as he’d toss the massively heavy timber into the truck bed with a resounding crash, I’d toss a few small sticks in. Helping daddy.

His face lit with the warmth of every sun in the galaxy when he’d tell that story, later on.

When I was born, my father David christened me “Jonathan,” because in the Bible, Jonathan and David were best friends. On the auspicious day that I turned one, dad ate my entire birthday cake. So much for the beautiful friendship, I told him when I was twelve or so. He thought this was highly amusing. I just wanted some more cake. Dad once stole ham from my eldest sister’s plate at Christmas. This somehow wound its way into our Christmas traditions. Some families sang carols under the stars, open mouthed and joyous; we hid ham from our father, and laughed in the dim glow of the multi-colored lights which festooned the perfectly enormous Christmas trees which he adored.

Dad liked to tell that story. He liked to tell many stories. There was his childhood, in the shadow of WWII, where trains carrying Sherman tanks rumbled by the family home in Sidney, Ohio, and where they took a trip to Camp Polk, Louisiana, for his father’s train-up. Those were tales of hot and dusty days, of leaping into foxholes between the Red and Blue “armies” in their maneuvers. Of lizards and airplanes and more tanks. Then there was after grandpa came home from the war, determined to never be cold again, moving the family to North Carolina. Fistfights in school because dad was a “Yankee.” Then the golden days of coming of age in the ’50s. So many stories.

And some that didn’t make sense as we got older. Was dad really going to go to Latin America in the ’60s to take part in some political revolution? Did he really meet Bobby Kennedy and get a promise to work with him? And what was that about the Russian embassy? We’ll never really know. But they were damn good stories. He lived and moved amongst them.

I was eight when we got our first TV. My uncle sent the small, brown set – with a VCR – so that we could watch Ken Burns’ “Civil War.” We all watched it together. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was to begin the hundreds of evenings of watching military documentaries and war movies with Dad. My poor mother had to deal with “Gettysburg,” “The Longest Day,” “Tora, Tora, Tora,” and “Patton” pretty much on loop. The river of her patience, might I add, is wide and deep. Dad’s two years in the Coast Guard Reserve gave him very little insight into war, and yet the topic fascinated him. He passed that along to me. And then had the nerve to be surprised when I enlisted in 2008. Mom was obviously not surprised at all. Moms never are.

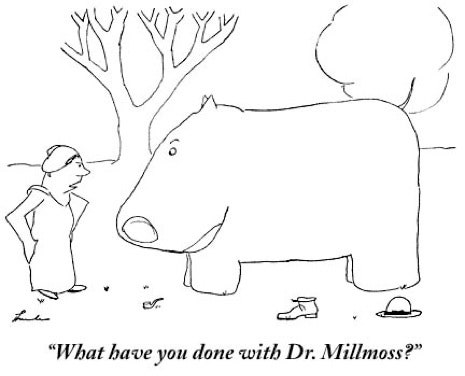

It wasn’t just war movies; there were nights of Laurel and Hardy, the Three Stooges, the Little Rascals, Andy Griffith, and other favorites from Dad’s own childhood, shared over large bowls of his popcorn, popped in a way that no human this side of the Beyond can make. He loved the absurd. Which is why he loved the writings of James Thurber so much – that, and his deep-abiding love for all things Ohio. He would sit in his big chair in the corner, snorting to himself over Thurber’s cartoon of a woman chiding a hippo-like creature, “What have you done with Dr. Millmoss?” We would throw Thurber quotations back and forth like a football, even to the very last weeks of his life.

Dad rarely had money in his pockets – said he didn’t believe in it. He carried beans, instead. They gave a better return on investment, he claimed. Dad spent his life waiting for the apocalypse – the end times – the final days. He collected weird books of prophecies purporting to be from Jesus and Mary, and discussed them with others who thought that there might be something in them. There was always talk occuring around dad, one could be sure of that. He could talk religion and politics until the cows came home. And then some more. “I love people,” he’d declaim, looking at me over the rim of his glasses with his sparkling blue eyes.

He truly did love people. Even when he disagreed with them.

As we both grew older, we argued, as fathers and sons are wont to do. Especially over religion. “Dad,” I snapped at some point in my all-knowing teens, as he was pontificating on a prophecy, “Nothing ever happens.” He’d quote this back to me in later years after nothing had happened, where he could own his mistake. And yet I’ve often yearned for his open-hearted faith. Perhaps it was the not happening that was dad’s greatest disappointment. In his own paradoxical way he desperately wanted the second coming of Jesus and the end of the world as we knew it; and yet for all that, he wished no harm to come to any person. He wanted the Great Tribulation, the final test – but not at the cost of human suffering.

Dad hated suffering. He’d remove struggling insects from water barrels, take spiders out of the house, and while he swore mightily at the varmints that molested his crops, he only used traps that didn’t harm the animal. He had an especial affinity for dogs. We had a whole passel of them growing up, mostly mutts of dubious heritages. But cats, too. Dad couldn’t bear to see an animal go unloved and so a parakeet, rabbit, and a pot-bellied pig came and went through the menagerie over the years.

Towards the end of his life, the farm became overrun with cats – largely because my parents would feed them. Dad would sit on his wrought-iron bench overlooking the sloping green of the farm, cats delicately rubbing their sleek lengths against his legs or rolling unceremoniously in the grass. He’d turn to me and say, “I’ve lived my life by the verse, ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and all things shall be added unto you.’ I never realized that ‘all things’ meant these derned cats.”

He sounds unbelievable. And the whole truth of the man, his entire paradoxical being, is less believable still. And yet it’s all true. He was a real, flawed human man. I am reminded of his flaws every time I reach for an alcoholic drink — and if my hand checks, it’s because I saw what the drink did to him. A man of deep passion and conviction, foiled and frustrated in his dreams, seeking strength in the bottle against the boredom innate to human frailty.

A real human.

And yet…what I remember of him is the deep sound of his laugh, his all-encompassing hugs, the smell of his popcorn, his strong soil-stained hands, and his startlingly bright eyes. I remember his deep and profound love for people, how he could never turn away anyone in need, how he would give away the fruits of his labor to anyone. And how he loved Christmas.

He, as a person, as a memory, as a sheer force of spirit, is so fully entwined in my existence that it does not actually make sense that he no longer inhabits this physical space.

For years, I’d expected the call from my mom. Any phone call from “Home” on my caller ID after 9 PM was greeted with a slight pause and clenched jaw. Dad was always terrible at taking care of himself. He’d almost died my freshman year of college, but recovered from that and got to enjoy sixteen years of watching his grandchildren grow up around him. But his health was never the same. His breathing got heavier and deeper over the years. But his grip – as he liked to point out – remained like a vice. His eyes – though more watery – still the intense blue that could freeze me right up as a rambunctious little boy, or greet me warmly coming home to visit. He made a point to always be waiting when I pulled up outside the house, coming home from wherever far-off place I’d been.

Living apart, we’d talk on the phone. Over the years, they became formulaic conversations. The old give and take. I can go into my voicemail even now and see the missed calls from him, from times when I was too “busy” to talk — a word he despised; busy-ness implied no time to live. Those hurt to see. Dad wanted community so much, but his family spread out over the earth. He loved when we were all together. “So,” he’d always close a conversation with, “when will we see you again?”

“I love you, dad,” I’d say, in diversion.

“You have no idea how much your daddy loves his favoritest man,” would be the reply.

He meant it, too. He might get angry, he might curse and swear, he might call God to task – a favorite diversion – over why someone was being so “dumb,” but he never stopped loving that person. The phone might crash down in anger in the moment but rest assured, it would be raised in apology soon after. He loved people, remember.

Easter Sunday, and I was putting planters full of seeds into the oven. I laughed as I did this and texted mom – dad’s advance into the digital age began and ended with the cordless telephone – to let her know that I was becoming dad. He and I were supposed to talk that day, but he was too tired. His breathing had gotten much worse and Mom grew concerned that he’d need to be hospitalized. This was our worst fear: independent, colorful, talkative dad, cooped up in a colorless and cheerless hospital, alone. During a pandemic.

To be safe, mom asked the parish priest to come over for anointing of the sick, a Catholic sacrament, and to give him communion. Then dad had a beer, laid down for a nap, and never woke up.

Dad always joked that he wanted to go out with his boots on, doing something heroic. Or, in his later years, to die down in his garden, amidst his beans. I’m exceedingly grateful that his wishes were not honored by the Authorities. Instead of being buried in his beans, he was buried in the small township cemetery, on the other side of the valley from where he spent his last quarter century. Overlooking his beloved Ohio fields.

In a way, he had his great tribulation that he prayed for. If you live your life expecting this time when all of heaven and Earth will be renewed and all things made new, to have the world continue on in business as usual is a great enough tribulation to endure. He endured suffering, much of it his own making, but isn’t that the story of humanity itself? Like his namesake, he was a broken, sinful man who walked and talked with the creator of the world.

My father left nary a cent. His inheritance was rescuing bugs from drowning in water barrels. It was seeing the beauty of a deep Carolina-blue sky, or the clearness of a piece by Borodin. It was the earth beneath our feet and the soil under our fingernails. It was beans in the pocket and a smile for those in need of it. His inheritance was kindness, thoughtfulness, and love.

Cover Photo: Photo taken by the author at the age of six.

One Reply to “”

Comments are closed.